Recently, something named the Large Bitcoin Collider (or LBC) has been getting some buzz due to its alleged ability to crack bitcoin addresses and take any bitcoin they contain. The LBC is using what is called the “brute force” method, which involves quickly trying every possible combination of numbers to find the solution. This is similar to guessing someone’s ATM PIN by trying 0000, 0001, 0002, and so on until the machine finally lets you make a withdrawal.

Does this mean that bitcoin addresses are under attack, or that the LBC will eventually rob a large number of bitcoin holders? Is there cause for concern? The short answer is no, not even a little bit. In this article we’ll undergo an exercise of examining very large numbers and breaking them down into meaningful analogies so that we can illustrate how immensely secure bitcoin is.

First, let’s talk a bit about what bitcoin addresses really are. To generate a bitcoin address, we start with a very large, random number, which we call the private key. We run this number through a mathematical formula to find the corresponding bitcoin address; the address is what you share with other people so they can send you money, and the private key is what you need to spend any bitcoin that the bitcoin address receives. If you know a private key that corresponds to a bitcoin address that someone else is using, you can take their money.

Paradoxically, there is nothing secret about bitcoin. Private keys are just large numbers within a predefined range, the formula used to calculate bitcoin addresses is well documented, and the entire record of which addresses contain funds is in the public for anyone to download and examine. Technically, you can simply choose a number, calculate the bitcoin address that corresponds to it, and if someone else is using that address the money is yours! What makes bitcoin addresses so secure, however, is that they hide in a sea of possibilities that is so astronomically large, that your chance of randomly guessing someone else’s private key is essentially zero, no matter how long or hard you look.

A typical bitcoin address looks something like this: 1G1W1DbeUeH2AKKicqMNuhEuaoqPDNuXDF. It uses numerals and upper- and lowercase letters to represent a very large number. In this case, the number being represented is 4,036,794,190,046,444,310,490,975,774,115,813,708,619,807,673,368,708,224,110.

Us humans have a very hard time visualizing numbers larger than, say, a couple hundred, so let’s do some thought exercises to imagine what we’re dealing with. The total number of possible bitcoin addresses can be expressed as 2^160. This is more than 1.46 x 10^48, a format you may remember from high school algebra. This means if you were to write out the full number, it would start with 146 followed by 46 zeros. So, how big is that? Let’s break it down like this:

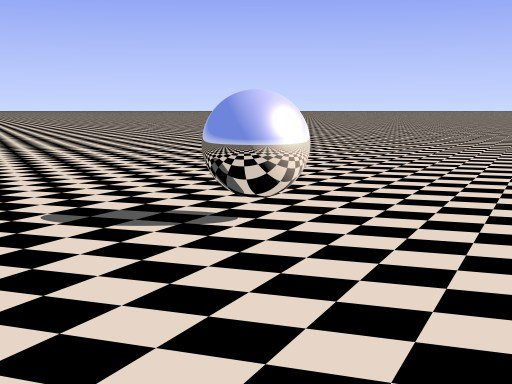

Imagine a chessboard with 1-inch squares. Each square represents a private key and its corresponding bitcoin address, and the board contains a square for every possible bitcoin address. Because there are 2^160 addresses, each side is 2^80 inches long.

How long is 2^80 inches? Well if you are familiar with light years (the distance that light travels in 1 year) then its 3,245,772 light years long. That means that if you were on a spaceship that could go the speed of light, looking for bitcoin addresses with money in them, it would take you over 3 million years* to check one column.

After just one second on your spaceship, you would have examined 11,802,852,677 squares on the chess board. 11.8 billion addresses seems like a lot, but remember that you are only 1 second into a 3 million year journey, which means that there are a lot of addresses to get through, even in one little column.

So let’s see what kinds of resources we can muster to search as many addresses as quickly as possible. The mother of all computational capacity is the bitcoin network itself, which uses the most powerful and highly specialized computers on the planet. The bitcoin network is about 100,000 times faster than the top 500 supercomputers combined, and for our purposes let’s imagine that we’ve convinced all of the hardware owners to loan us their equipment for our experiment.

The bitcoin network today could search through about 4,000,000 trillion (4 quintillion) squares on the chessboard every second. That sure is a lot faster than our little spaceship! And at that speed, how long would it take us to check one full column on the chessboard? The answer is about 3.5 days—a huge improvement over 3 million years!

But we need to understand what we’ve actually accomplished. First, it cost us $7.5 million in electricity, so it’s been a pretty expensive few days. And what was our haul? How many bitcoin addresses were we able to swipe coins from? The answer is zero. We found no bitcoin addresses that had funds in them.

To understand why, we need to get a sense for just how few of the possible bitcoin addresses actually contain funds. Today, the total number of addresses with some funds is about 5 million. That means that in the gigantic chessboard we’ve constructed there are 5 million potential targets. 5 million on its own sounds like a large number, but how many columns would you have to search through before you could statistically expect to land upon your first prize? You would have to go roughly one 5 millionth of the way across, and one 5 millionth of 2^80 inches is about 2^58 columns. OK, so we know how far we have to go to find our first lucky address, but how long is it going to take us to get there?

At the rate of 1 column every 3.5 days, we’re getting through approximately 100 columns per year. So it’s going to take us about 2^51 years until we strike gold. But how big is 2^51? It’s 2,250,000,000,000,000 or 2.25 quadrillion years.

Keep in mind that the entire universe is only 13,800,000,000 or 13.8 billion years old. If you were to start your quest for finding funded bitcoin addresses at the beginning of time, using the full power of the modern-day bitcoin network, as of today you would be only 0.0006% of the way towards finding your first funded bitcoin address. You would have checked 1.4 trillion columns on the chessboard, each containing 2^80 squares, and still be nowhere close to robbing a single address.

How pathetic is 0.0006%? Mt. Everest contains about 7.25 million cubic feet of rock. For all of your efforts since the beginning of time, you would have mined 44 cubic feet of worthless stone, which is about the size of a modest dressing table at 3.5 feet per side, and you would still need to grind your way through the entire mountain before finding your first funded address.

And in actuality, brute forcing bitcoin addresses is even more complicated. The number of possible private keys is monumentally larger than the number of possible bitcoin addresses, so multiple private keys map to the same bitcoin address. This means that much of your work is theoretically redundant and a waste of time and energy.

But hang on! Didn’t the LBC already find some bitcoin addresses with funds? Yes, but there is a catch. A tiny number of funded bitcoin addresses have been purposely made with what’s called “poor entropy,” which means the numbers used as private keys were not very random. This is the same as trying to brute force someone’s ATM PIN, when they were lazy and chose to use the sequence 0000 instead of using something more unique. By starting the search in an area of our chessboard that represents logical patterns that are meaningful to humans, the LBC has been able to pick up a few bits here and there, but these spoils were essentially meant to be found. Also, remember that the LBC searches much more slowly than the bitcoin network could. How many addresses has the LBC checked so far? 1,000 trillion. That is barely one day's worth of hunting bitcoin on our light-speed spaceship.

With all serious addresses using truly random numbers, the LBC’s threat to bitcoin holders of the world is essentially nonexistent.

*Because of relativistic complications regarding time and the speed of light, all mentions of time are from the perspective of an observer standing still on the chessboard (thanks u/sorrillo for pointing out this detail).